WOMEN MOBILIZING MEMORY: Patricia Ariza on Culture as a "form of resistance"

TRANSFORMING TRAUMA WITH THEATRE

“Culture is a form of resistance,” asserted Colombian playwright, director, producer, and actor Patricia Ariza as she met with twelve members of the Center for the Study of Social Difference's Women Mobilizing Memory working group at the Hemispheric Institute in New York City.

Ariza was recently in town to accept the 2014 Gilder/Coigney International Theatre Award from the League of Professional Theatre Women but she took time to discuss with the group her near fifty years of work employing theatre to promote social justice, particularly as it applies to Colombian politics, political violence, and women. Ariza is co-founder of the highly influential Teatro La Candelaria, Colombia’s first independent, experimental theater, and for the past 25 years has focused primarily on women and social justice, empowering traumatized citizens to express through public performance their experiences during the massive violent conflicts that have rocked Colombia for decades. These performances help transform pain into something socially constructive, she said.

Ariza showed a video of an encuentro, or action, she orchestrated in 2009 at Plaza de Bolívar in Bogotá where 300 women, mostly survivors of political violence and family members of deceased/disappeared victims, grieved and memorialized for a whole day the systematic assassinations of political leaders throughout the country. Civilian demonstrators joined by theatrical performers chanted “Dónde están?” (“Where are they?) as they carried photos of their missing and murdered relatives. Ritualistic choreography accompanied by fandango drummers and piano culminated in one dancer climbing atop the statue of patriarch Simon Bolívar. Participants stepped through life-sized silhouettes of the bodies of the victims as a song instructed the mourners, “If you want to sing, sing/If you want to cry, cry.” Many did just that.

A DIFFERENT WAY OF INHABITING PUBLIC SPACES

Speaking through a translator, Ariza said that originally she did not intend to devote the last quarter-century to doing memory work with victims groups. “At first, I thought it was an act of generosity,” she said, “but then little by little it came to me that they provide a special, deep knowledge—a different way of doing political actions…and inhabiting public spaces.”

Ariza told the group that only recently have women been permitted to politically inhabit public spaces like town squares, which have historically been reserved for male-oriented political and military purposes.

“Art can help a lot,” said Ariza, who said cultural actions and celebrations are important sites of resistance against political oppression and violence. “It can get people to stop thinking war is the solution. You can’t do that through laws—only through culture,” she said.

With a slightly bowed head and limited eye contact, Ariza discussed another action that memorialized the government-approved murders of approximately 4,000 members of the left-wing U.P. (Patriotic Union) party in the 1980’s. In the action, 1,050 U.P. survivors stood at 1,000 candlelit tables in Plaza de Bolívar wearing the clothes of the deceased and placing their possessions on the tables. She said people came from all over Bogotá to see the performance, which was repeated for three years.

A spirited discussion ensued after Melody Brooks, co-chair of the Gilder/Coigney Award, inquired about the U.S. “Plan Colombia” that funds military missions against drug cartels and left-wing insurgents. Ariza said that the Colombian military has provided ersatz results by perpetrating approximately 4,000 murders of “false positives”—innocent citizens falsely characterized as drug traffickers or insurgents.

Ariza said that in an effort to aid Colombia’s compromised peace process, she hoped to plan an international peace summit of women in theatre in New York in April 2015.

Contributed by Terry Roethlein, Communications Manager, Center for the Study of Social Difference

Image of Patricia Ariza, center, at the Hemispheric Institute Encuentro in Bogotá, Colombia, 2009, by Cristhian Ávila.

Female Leadership, Labor, and Women's Lives in India

Anupama Rao, Project Director of the Women Creating Change working group "Gender & the Global Slum" reflects on female leadership, labor, and women's lives in India.

There are a number of contradictions that organize women’s lives in India today. The conditions and consequences of women’s work is a central one among them.

Female labor is not rare, neither is it new: women are overwhelmingly responsible for all manner of ‘care work’; they are employed in low-productivity agriculture and small-scale manufacturing; and they are present in large numbers in call centers. Women also occupy prominent decision-making roles in politics, and in the private sector. That is to say, neither women, nor the work that women do is invisible.

So far as education is concerned, new studies confirm that there exists no “gender gap” between the performance of boys and girls including in fields such as math and science until the onset of puberty. But it does not stop there. Studies also suggest that young women are significantly outperforming their male counterparts in high school and college, so much so that the underperformance of boys and young men—and its impact on gender relations more broadly—is now a topic of concern.

Yet a recent study found that female participation in the Indian economy, i.e., paid work outside the home, is among the lowest in the emerging markets and declining. Only about six percent of women are employed in the formal sector with access to social benefits, such as pensions or maternity. In the informal sector which employs the majority of Indians, whether men or women, women’s wages are half that of men’s. OECD calculations show that growth could be boosted up to 2.4% points with a package of pro-growth and pro-women policies.

Though enormous, the challenges women leaders face must be viewed against this backdrop of the under-valuing of female labor more generally, combined with the discrimination faced by women in all sectors of the economy with respect to equal pay and benefits.

Challenges to female leadership:

Below I outline a number of challenges specific to female leadership as a set of possible talking points for discussion. As will be obvious, they span the structural hurdles women face, as well as cultures of the workplace and workplace etiquette, issues which falls into the grey area of behavior, stereotype, and expectation:

a) Female leadership as a model of fire fighting, with women brought in to manage situations of crisis. For example: Lynn Laverty Elsenhans took the helm of Sunoco after shares had fallen by 52%; Marissa Mayer was hired to save a struggling Yahoo; and Mary Barra was appointed to the top seat at GM just weeks before its ignition-switch investigation

b) This is connected to this is the assumption that female leadership is “nurturing,” and helps to humanize companies and corporations. (Of course the other side of this logic is that women lack the competitive spirit to run companies with a firm hand, with an eye towards profits.)

c) Since women in positions of leadership are still rare, they often become tokens, isolated from other women due to the demands made on them for appropriate behavior.

d) Women find themselves excluded from spaces where networking occurs whether sports, late night dinners, or other kinds of “old boy networks” that are inimical to the presence of women. Juggling home and family, or the fact that women may not be interested in sports and other forms of socializing means that they may be missing from key social contexts that extend beyond the workplace, but function as an extension of the boardroom.

e) Women leaders are often subject to gender stereotyping. They are viewed (by both men and women) as aggressive, or they are subject to extra scrutiny because they are seen to be emotional, irrational, or less competent than men.

f) Women often lack strong role models and lack mentors who can illuminate work culture and expectations that are usually implicit, rather than explicit

g) Company culture does not support work/life flexibility that can be essential to women, and rarely are women provided the social benefits they require to balance expectations at home and at work. If women do make the decision to take a break in their career, or to consider flexible work options, their loyalty and commitment is questioned.

What do we need?

1) A model of nurturing female leadership from within, with gender-positive models that encourage women to support each other’s careers, and to challenge the tokenism that pervades the rhetoric of gender inclusion.

2) Developing women’s sense of worth and confidence in their judgment is a necessary corollary to their ability to model positive behavior for younger women.

3) Stronger workplace regulation, prevention from harassment, and the institution of structures of accountability and transparency would go a long way in enabling a level playing field in the workplace for women and minorities.

4) Women in the public, formal sector should recognize the unequal labor conditions, and the situations of risk and precarity under which most women (and many men) work. The recognition of connections between broad inequities, on the one hand, and gender discrimination within the workplace on the other, is essential for creating a strong sense of corporate responsibility on the part of women leaders who are in a position to draw on their own experience to push for social benefits for others.

Anupama Rao is Associate Professor of History at Barnard College; a member of the Executive Committee for Women Creating Change and Senior Editor for the journal Comparative Studies in South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

VIDEO: "Gender, Memory, Activism"

Women Mobilizing Memory workshop: "'Coming to Terms' with Gendered Memories of Genocide, War, and Political Repression," featuring Marita Sturken, Marianne Hirsch, Nükhet Sirman, Meltem Ahıska, and Nancy Kricorian. Istanbul, Turkey, September 2014.

VIDEO: "Art, Performance, and Memory"

Women Mobilizing Memory workshop: “‘Coming to Terms’ with Gendered Memories of Genocide, War, and Political Repression,” featuring Andreas Huyssen, Alissa Solomon, Carol Becker, Diana Taylor, and Maria José Contreras. Istanbul, Turkey, September 2014.

VIDEO: "Creating Alternative Archives"

Women Mobilizing Memory workshop: “‘Coming to Terms’ with Gendered Memories of Genocide, War, and Political Repression,” featuring Leyla Neyzi, Susan Meiselas, and Silvina der Meguerditchian. Istanbul, Turkey, September 2014.

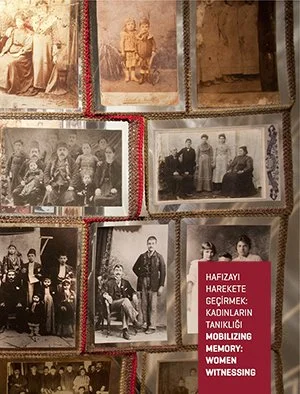

"Mobilizing Memory: Women Witnessing" EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

Opening Reception: September 5, Friday, 18:30

Venue: DEPO Istanbul (Lüleci Hendek Cad. 12, Tophane - Istanbul)

Artists: Gülçin Aksoy, Hera Büyüktaşçıyan, Silvina Der-Meguerditchian, Hakikat Adalet Hafıza Merkezi (Truth Justice Memory Center), Gülsün Karamustafa, Susan Meiselas, Nar Photos (Serra Akcan, Fatma Çelik, Gülşin Ketenci, Aylin Kızıl, Serpil Polat), Lorie Novak, Emine Gözde Sevim, Aylin Tekiner

View exhibit catalog here (PDF)

Curated by: Ayşe Gül Altınay, Işın Önol

What is the role of witnessing in practices of resistance: resistance to enforced silence and forgetting, to state power, and to inaction? What role do the arts play in combatting the erasure of past violence from current memory and in creating new visions and new histories for future generations? In particular, what unique strategies have women devised to reveal and redress the violence directed at woman and at other disempowered social groups?

The feminist art work displayed in this exhibit imagines memory as part of a larger politics of resistance. It mobilizes memories of past and present violence precisely to create the conditions and the motivations for social change. Bringing together women artists many of whom are themselves direct witnesses to oppression and terror, the exhibit also reveals moments of resilience, resistance, and creative survival. The artists gathered here use memory in innovative ways. They foreground unofficial acts of witness and forms of commemoration--embodied practices, performances, photography, testimony, street actions—that provide alternative histories and different political imaginaries than do official archives, memorials, museums, and state commemorations. They make visible not only violent crimes and their gendered dimensions, but also the intimate texture of lives and communities that have survived or are fighting to survive immense destruction. In honoring those lives and bringing them out of oblivion, the artists also reclaim women’s practices—dance, song, embroidery, for example—and show their political resonances. As a group, these artists resist monumentality in favor of intimacy, featuring individual stories of the quotidian. They use official archives to document and contextualize those lives, but they also create new archives and alternative interpretations, reframing how we understand the past and pointing to what has been excluded from authoritative histories. They thus imagine alternative social and political trajectories and more open and progressive futures.

This exhibit occurs in the context of a five-day workshop on “Mobilizing Memory for Action” that brings together an international group of scholars, artists, and activists to analyze the activist work memory practices can enable. The art works comprising this exhibit and the broadly comparative panels and roundtables on September 17 invite us to ask how our acts of witness can motivate social change. What do images and accounts of past and present violence demand of spectators, listeners, and readers? How can we modulate proximity with distance, empathy with solidarity? Indeed feminist practices of witness have fostered solidarity that demands not only collaboration and commitment, but also a respect for what is historically specific to particular acts of violence and oppression. In bringing diverse events of state violence—the Holocaust, the dictatorships in Latin American, American slavery—to the Armenian genocide, the persecution of Kurdish and Palestinian communities, and the oppressive acts of authoritarian power featured in this exhibit, the “Women Mobilizing Memory” workshop invites participants both to see where connections lie and also to recognize what cannot be generalized or translated across linguistic, national, or religious borders. In resisting silence, forgetting and erasure, progressive acts of memory also resist easy understanding, appropriation and straightforward comparison.

The collaborations among the participants in the working group, and between the artists and their subjects, aim to create a space of solidarity and connection. We invite you to enter into this larger collaborative project of responding to the memories recorded here, and to join us in the work of shaping memories for more hopeful futures.

Co-hosted by Columbia Global Centers | Turkey, DEPO Istanbul and Sabancı University Gender and Women's Studies Forum, the exhibition and parallel activities have been supported by the the Center for the Study of Social Difference, Blinken European Institute, Sabancı University, Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics, the Truth Justice Memory Center and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Turkey Office.

For more information about the project please visit: http://socialdifference.columbia.edu/projects/women-mobilizing-memory

Lila Abu-Lughod & Susanna Ferguson: On "Debating the 'Woman Question' in the New Middle East | Women’s Rights, Citizenship, and Social Justice"

May 3-4 2014

Columbia Global Center | Middle East (Amman)

On May 3 and 4, 2014, the Columbia Global Center | Middle East in Amman hosted a workshop entitled “Debating the “Woman Question” in the New Middle East: Women’s Rights, Citizenship, and Social Justice.” The workshop was part of a larger project on “Gender, Religion, and Law in Muslim Societies” of Women Creating Change, an initiative at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Social Difference. Lila Abu-Lughod (Columbia University), director of the WCC project, co-organized it with Safwan Masri (Director of Columbia Global Centers), Amal Ghandour (Special Advisor to the Global Center in Amman), and Hoda El Sadda (Cairo University) with funding from Women Creating Change, the Blinken European Institute, and the Columbia Global Center | Middle East in Amman.

The aim of the two-day workshop was to bring together scholars and practitioners with expertise in the field of women’s rights and development to assess the impact of the Arab uprisings and their aftermaths and to take stock of emerging debates in the Arab world about women’s rights, citizenship, and prospects for justice. The international group of 20 participants came from five countries in the region as well as the US and UK. All had ongoing research and practical experience in the Arab world. It was particularly exciting to hold the discussions in Amman, Jordan, as we could draw in a strong contingent of Jordan-based participants with insights into the dynamics of local feminist debates

The intent of bringing together these interdisciplinary experts from the region was to move beyond superficial culturalist explanations that are popular in the West—attributing women’s status and prospects, for example, to the constraints of Arab culture or Islam—while also critically examining a tendency in the Arab world either to view women’s rights as mere tools of cultural imperialism or to imagine a simple opposition between women’s rights and Islam. These scholars and practitioners were knowledgeable about the many ways in which Arab women have been engaged in political activity, whether through street protests, human rights groups, feminist projects of legal reform and empowerment, or in the everyday contexts in which political contests have been occurring and Islamic parties and discourses have gained strength and legitimacy.

Three themes organized the discussions: the role of political economy and colonial processes in shaping gendered lives, bodies, and politics; the effectiveness of legal strategies for citizenship and justice, particularly for women; and the impact of Islamist governance and the rise of Islamic feminisms on women’s lives and rights.

Political Economy and Embodied Lives

Nicola Pratt argued for the importance of political economy in structuring gender relations in Egypt both prior to and after 2011, showing how the withdrawal of the state from key social services has put more pressure on the family as an economic unit. Consequently, women bear the heavy “double burden” of wage work and household labor while young people have been trapped in long periods of “waithood,” unable to marry and start families of their own. In turn, these dynamics have created a disjuncture between the roles that both men and women are expected to play (breadwinner, home-maker) and what they can actually accomplish, whether in the workplace, the family, or the home. This disjuncture, Pratt argues, is critical to understanding the 2011 uprising in Egypt and its gendered aftermath as different strategies for stabilizing gender relations have emerged: one, represented by the Muslim Brotherhood, has responded to economic hardship with promises to restore the “ideal family” by promoting conservative gender norms, while the other, represented by young activists (many of whom are women), has insisted on the continued presence of women in the public sphere.

Sara Ababneh joined Pratt in arguing that questions about political economy should be central not only to our analyses of world-historical events like the Arab uprisings, but also to our political interventions. By highlighting a lack of overlap and solidarity between Jordan’s feminist movement and the women and men of the day-waged labor movement, the hirak sha’bi, Ababneh asked us to consider how an exclusive focus on “women’s issues” has prevented middle-class Jordanian feminists from hearing or supporting the demands expressed by both men and women in the hirak sha’bi for a minimum wage, paid holidays, and job security. Her observations about the disjuncture between mainstream Jordanian women’s NGOs and the day-waged laborers raised the crucial question that would run throughout the discussions at the workshop: feminism’s potential exclusions. How might a politics structured around “women’s rights” exclude or render unintelligible concerns about livelihoods and economic wellbeing shared by both women and men? How could feminists in Arab countries, as elsewhere, not be blinded by their class origins and easy turn to the political rather than the economic? Jordanian feminist Hala Ghosheh built on these concerns and on Ababneh’s reflections to pose another difficult question: had some feminist organizations in Arab countries been made complacent and ineffective not only by deep investments in the economic status quo, but also by their close relationships with ruling regimes? Might traditional feminist projects rooted in the middle class and sanctioned by ruling elites be usefully complemented, or replaced, by a more grassroots approach?

If Pratt and Ababneh argued that political-economic concerns should be central to our modes of analysis and political interventions, Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian showed how sedimented histories of legal and political as well as economic oppression continue to structure the intimate lives of Palestinian men and women. Her focus was the gendered yet deeply politicized processes of pregnancy and giving birth in occupied East Jerusalem. Her paper showed the importance of looking “across historical tenses,” as she linked the legal categorization of Palestinian women who returned home after 1948 as “infiltrators” to the current challenges faced by pregnant Palestinian women who must navigate contested political spaces and borders to ensure legal that their children receive legal recognition from a hostile Israeli state. More importantly, Shalhoub-Kevorkian reminded us that it is in the most intimate spaces of (gendered) life and mobility that we can see how histories of injustice and oppression shape women’s embodied lives.

In their papers, Frances Hasso and Zakia Salime reinforced the value of this other dimension of the material: “the gendered body” as an analytic for understanding contemporary dynamics and transformations in the Middle East. For Hasso, gendered and sexualized bodies and the spaces through which they move (or are prevented from moving) offer a productive lens for thinking through the 2011 uprisings in Egypt. These uprisings featured diverse and mutable actors and constituencies (for example, “the people,” or al-sha’b) rather than the unified entities that have been central to traditional historical and sociological analysis (for example, “the working class”, “the army” or “the state”). Building on Jacques Ranciere’s concepts of “politics” and “police,” Hasso argued that only by thinking about specific gendered bodies and the particular contours of revolutionary spaces (think, for example, of Tahrir square) can we begin to understand Egypt’s 2011 uprising and its aftermath. In particular, it is critical to think about gendered bodies and their specific positioning vis à vis shifting relations of power to see how even “revolutionary” or emancipatory forms of politics may continue to enact hierarchies and exclusions, with detrimental implications for women and others who inhabit bodies that get marked as “other.”

For Zakia Salime, as for Hasso, attention to the gendered bodies of ordinary women enables us to think about how women have influenced, participated in, and lived through this particular moment in the Arab world. Salime focused on two provocative examples from Morocco--the self-immolation of Fadwa Laroui in 2011 and the suicide of Amina Filali in 2012-- to argue that ordinary women who are not always represented by mainstream feminist groups are turning to embodied acts like self-immolation and suicide to “express a sense of self-worth and rights,” and to intervene politically in contexts which sometimes take women’s political representation seriously but fail to meet the demands and desires of ordinary women. For Salime, Laroui’s videotaping and first-person narration of her own self-immolation suggested a desire to produce her death as spectacle, to use her body to draw attention to the impossible circumstances of single mothers in Morocco and inspire others to “take a stand against injustice, corruption, and tyranny.” Laroui’s act, however, did not spark the same controversy as the death of Amina Filali, who committed suicide after being forced to marry her rapist in March of 2012. This proves that positionality still matters even as “ordinary women” take matters into their own hands: the death of Laroui, a working-class single mother whose concerns were about livelihood and social welfare, received much less attention than Filali’s, which fit into dominant international narratives about female “victims” of male aggression and of patriarchal “Islamic law.” Salime also countered this narrative about Filali as a “victim” of patriarchy and Islam, suggesting instead that her death might have been made possible in part by the erosion, under neoliberalism, of traditional “patriarchial” structures that served to protect women in the past.

A key debate that emerged from these analyses of history, the body, and political economy was about the significance and meanings of gender as a category of analysis and a focus of activism. While Pratt and Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s work, for example, suggested the inextricability of gender from historical and contemporary structures of political-economic oppression, Ababneh’s reflections on the gap between middle-class Jordanian feminists and the women and men working on questions of livelihood in the hirak sha’bi reminded us that using gender as the primary scholarly analytic or political focus might preclude broader solidarities and also render invisible or unintelligible important struggles that do not articulate themselves in gendered terms. Leila Hilal’s suggestion that women in particular have great potential as peacemakers in contemporary Syria compelled participants to ask how and under what circumstances gender should serve as a dominant lens for conceptualizing political possibilities and action.

Hasso suggested that an analytic focused on gendered and sexualized bodies and spaces might offer us a way of thinking not only about women but also about men, while Salime argued that larger social problems and dynamics are mediated through women’s bodies in particular ways. The conclusion was that lived material conditions and the histories and structures of oppression impact intimate lives and embodied realities, which are indeed gendered. How to conceptualize political transformations and dynamics, including those of class and ethnicity, by thinking through intimate, everyday life and the gendered body emerged as crucial arenas for future scholarly and political work on women in the Middle East.

The Effectiveness of Legal Strategies

The second of the workshop’s organizing themes centered on how effective for women were legal strategies for citizenship and justice. While all agreed that the law has been a central arena for feminist intervention in the Arab world, as elsewhere, tough questions arose about the roles law does and should play in future feminist politics and practice. In the case of Palestine, Reem al-Botmeh noted the depoliticization and NGO-ization of the Palestinian civil sphere that has accompanied the rise of legal reform as central to Palestinian governance and gender advocacy. In her view, this focus on the law has obscured the difficult political work which remains to be done both for women in Palestine and for Palestine in general. She also reminded us that the law does not always do the work it claims to do, particularly for women. Her research showed that while the shift from shari’a (personal status) courts to civil courts in Palestine was presented as a triumph for women’s rights, in practice it has made it more difficult for women to access justice in the courts; the civil legal apparatus has proven both more rigid than that of the shari’a courts and more dependent on expensive legal expertise that poor women cannot afford.

Likewise, Susanna Ferguson argued that the invocation of human rights and international law as a primary language of justice by feminists in Syria had both emancipatory and disciplinary effects. While articulating feminist claims and political desires in the legalistic language of rights promises to give citizens a framework within which to demand new freedoms from the state, these invocations of rights also structure the subjectivities of those who speak in their name, creating new silences and exclusions. In pre-uprising Syria, making claims in the language of rights produced subjects who had a faith in modernity and progress and an aversion to tradition. Confident in the promises of the nation and the universals represented by international conventions, they distanced themselves from what was deemed “religious” in favor of what was considered “secular.” These convictions may have prevented advocates of “women’s rights” from engaging with women across the country who did not share these certainties.

At the same time, many contributors re-affirmed the power of the law to serve as a vehicle for women’s empowerment. Marwa Sharafeldin argued that in the case of the 2006-2010 campaign to reform Egypt’s Personal Status Law, both human rights law and Islamic law served as important resources for women’s NGOs. The way in which these NGOs appropriated concepts from both legal discourses to support their reform agenda revealed the potential for creative and syncretic political platforms that draw strength from multiple legal traditions. Activists were able to turn to the law (in various forms) to respond to the challenges they observed Egyptian women facing in their daily lives.

Nabila Hamza and Hoda El Sadda followed Sharafeldin in arguing even more firmly that law is key resource for women. Hamza argued that in the case of post-revolution Tunisia, international human rights law served as a crucial resource for feminist activists as they helped to draft a new constitution. In particular, it enabled them to remove any references to shari’a law from the 2014 Tunisian constitution and to push for an article that pledges that the state will seek to guarantee parity among men and women in elected councils, protect women’s rights, and take measures to eliminate violence against women. Likewise, El Sadda, a feminist scholar and activist who was on the 50-person committee tasked with writing a new constitution for Egypt in 2014, described how she was able to form coalitions with other power brokers during the drafting of the new constitution by appealing to the law and to a language of rights. Acutely aware of the compromises and shortcomings of the process, she nevertheless was convinced that the law in this instance was both an important tool and a critical arena in which feminists were able to engage with existing structures of power to further a feminist political agenda.

A wide variety of perspectives emerged about the role the law and the framework of women’s rights should play in future scholarship and political work.

Islamic Governance and Islamic Feminisms

A third theme of the workshop was the impact of Islamist governance and the rise of Islamic feminisms on women’s lives and rights in the region. Yara Sallam from the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) argued that because they had decided not to engage with legal or political questions emanating from interpretations of Islam, secular women’s NGOs in Egypt after the 2011 uprisings were unprepared to contest the agenda put forward by ex-President Mohammed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. She suggested that women’s NGOs needed to be able to engage more effectively with political Islam on a policy level, rather than leaving the field of interpreting Islam to Islamist parties and the women and men who belong to them. Marwa Sharefeldin, speaking as a scholar and a member of Musawah, pointed out that there is a stronger alliance now than there was in 2012 between feminists making arguments in Islamic terms and women’s NGOs.

Merieme Yafout, however, reminded us not to lump together the women who belong to “Islamist parties” either across the region or within individual countries. Opinions about correct interpretations of Islam and the shari’a, as well as the best forms of political engagement, vary widely among women who belong to the region’s many Islamist parties. Serious contestations are taking place among men and women within the sphere of political Islam about correct interpretations and ways to proceed. Yet, Yafout’s research in Morocco and Tunisia showed that the 2011 uprisings have ushered in a new phase in which women are taking on more public roles in Islamist political parties.

Like Yafout, Asef Bayat argued that the 2011 uprisings and women’s very public participation in them have released new energies and opened up new possibilities and challenges in the Middle East. While, in his view, the presence of women in the public sphere was central to de-exceptionalizing and broadening the uprisings, many women have also faced new kinds of violent backlash against their presence in the public sphere. Nevertheless, this revolutionary moment in which so many conflicting tendencies have found free expression may have opened up further possibilities for the emergence of what Bayat termed a “post-Islamist” polity, which favors a non-religious secular state, a neoliberal economy, but a religious society. The impact of this kind of conjuncture has yet to be parsed for women and for advocates of liberal democracy in the region. One political possibility is that both men and women will continue to participate in what Bayat terms “non-movements,” in which non-collective actors engage in ordinary actions that shift conservative norms and enhance citizenship in practice, destabilizing or challenging structures of power.

Conclusions

These questions about the focus, strategy, and language of women’s political participation framed a larger conversation that took place among many of the workshop’s particpants regarding what can or should constitute feminist political intervention. Both Zakia Salime and Lila Abu Lughod raised this question explicitly, wondering, who intervenes on whose behalf under the aegis of feminism and women’s rights, and on what grounds? Samar Dudin described her “6 Minutes Joy of Reading” campaign, which gives Jordanian women from the Jabal al Natheef neighborhood in East Amman an opportunity to read short stories, novels, and poetry in addition to the religious texts to which they normally have access. She argued that this project constituted a model of local and accountable feminist intervention in women’s lives through literature, as women, teachers, librarians, and youth in the community worked together to address a problem that they observed in their neighborhood and meanwhile to build community leadership. Abu Lughod asked, however, if even this grassroots project might still be claiming to intervene, on behalf of a secular women’s rights vision, among women who may not desire or require such an intervention.

A set of serious and respectful debates like this one animated the workshop. There was total agreement about the value of comparative study to illuminate differences among the situations in different countries--Egypt, Tunisia, Syria, and Palestine, for example. The importance of transnational flows and conversation in having advanced the “Arab spring” and feminist projects also became clear. The deep regional knowledge of the “lived realities” that participants brought to the discussions confirmed the value of thinking historically about gender and its transformations rather than reverting to timeless cultural patterns for explanations. Participants like Amal Ghandour remarked on the rich political landscape and extraordinary differences among countries. Hoda El Sadda also pointed to the challenges that the fast pace of change and the constant shifts in policy and politics in the region had presented to old paradigms and strategies. Ahdaf Soueif noted that even some of the most negative developments—like the deliberate sexual assaults targeting in Egypt—had led to breaking taboos about speaking up, which then paved the way for an article in the new Egyptian constitution explicitly condemning violence against women for the first time. Both scholars and practitioners benefitted from the opportunity to engage one another in a substantive way and to talk about translating, as Hala Ghosheh put it, “across domains.” From this group of committed scholars, it was clear how problematic it was to distinguish among scholars, practitioners, activists, and “ordinary” people.

Although they spoke from different geographical, political, and methodological locations, the workshop participants shared a commitment to justice and fuller citizenship. The question was how best to achieve this ideal. Questions about gender were raised alongside questions about material realities and intimate, everyday lives; possible ways of confronting the power of states, police forces, armies, neoliberal regimes and geopolitical interests; the role and work of the law and other languages of justice; and the impacts of Islamic feminisms and politics.

The fissures emerged in debates about the power, exclusions, and politics of the different languages of justice operating in the region; about who is able to access what kind of law and how law and legal reform work in practice; about how to understand and whether to deploy Islamic language and practice in political work; and about the significance and meanings of gender as a category of analysis and focus of activism. Disagreements emerged about the value and dangers of various forms of intervention meant to enhance women’s rights and livelihoods, forcing us to consider which women and which social groups they might exclude, either deliberately or inadvertently, whose interests they serve, and which arenas and domains--the economic, the political, the intimate--should be the focus of our analysis and our short- and long-term efforts, given the geopolitical forces with which people in the region must contend.

Lila Abu-Lughod and Susanna Ferguson

Women Mobilizing Memory Workshop II

Working group:

Women Mobilizing Memory

Hemispheric Institute for Performance and Politics Encuentro

Montreal, June 2014

Conveners: Marianne Hirsch, Jean Howard, Diana Taylor

Description:

Bringing together artists, writers, theater practitioners, museologists, social activists, and scholars of memory and memorialization, “Women Mobilizing Memory” focuses on the political stakes and consequences of witnessing and testimony as responses to socially imposed vulnerabilities and historical trauma. The working group will probe how individual and collective testimony and performance can establish new forms of cultural memory and facilitate social repair. Using gender as an analytic lens, this project explicitly explores women's acts of witness and the gendered forms and consequences of political repression and persecution. It asks what strategies of memorialization and re-imagining are most effective in calling attention to past and present wrongs and in creating possibilities of redress through protest and other forms of action and resistance.

Participants:

Pilar Riano, ‘Afro-Colombian Singing as Testimonial Practice.’

Giselle Ruiz, ‘A Poetic Corporeality’

Victoria Fortuna, ‘Dance Based Memory Practice’

Ausonia Bernardes, Memory in Contemporary Dance Practice.

Monika Gagnon, "What is Posthumous Cinema?"

Barbara Sutton, "Women Mobilizing Body Narratives of State Terrorism in Argentina (1976-1983)"

Julie Okotbitek

Milena Grass, “Women who collaborated with the dictatorship”

Raúl Diego Rivera Hernandez, “Performative strategies of Central American Caravan of women searching their missing relatives in Mexico”

Nuria Carton de Grammont —narco trafico

Leticia Robles, “Antigonas”

Carolyn Vera, Guatemalan performance artists

Leyneuf Tines Villarraga, TBA

activistas / desafíos políticos.

Shahrzad Arshadi

Lorie Novak, “Photographic Interference”

Jenny James, "Bricolage Memories: Gender, Refugee Life and Narrative Repair in the fiction of Dionne Brand and Kim Thuy"

Magdalena Olszanowski, ‘Between Mother and Daughter: The belly button as scar of separation’

María José Contreras, ‘Teatro testimonial de mujeres ancianas mapuches’

Methodology:

We spent each of the sessions on a particular topic arising from the participants’ interests. Beforehand we circulated by internet brief background readings for each session and for the group. Each session we had a warm up exercise in order to create a collectivity that could think and be in presence together Then, each participant presented a 6 minute presentation that ended with questions for a 3 minute discussion. Each session concluded with an extended 45 minute discussion.

Some notes about our discussions:

As said in the call, the group discussed about the role women in the circulation, recovery, reshaping and mobilization of memory.

Some of the most important issues that emerged during our work was COLLABORATION. Collaboration was seen in different levels: between women that had suffered violence, but also between women artists and/or activists and/or researchers with women that had survived to violent pasts. Women’s memory practices may enable transnational memory networks, both at a local and global dimension.

We also considered posthumous collaboration, as a way to connect the living and the death. Some of the case studies discussed evidenced how the dead spoke to us through their traces. In a sense, when studying memory of violent pasts, all collaborations are somehow posthumous, they are about what remains and what may survive.

MEMORY was defined as a practice that sometimes allowed the cultural renewal of traditions and sometimes functioned as resistance to narratives of disposability or vulnerability. Memory practices appeared as crucial strategy of resistance for women who have endured continued forms of physical erasure (from genocides to current femicides),

Art and cultural performances recuperate and reshape memories. Memory is not just about bringing stories, is about creating a collective history. In that sense, memory is always intervening in the present creating new forms of identity and collaboration. The mobilization of memory allow different possibilities for an engagement that triggers multiple plural ways of seeing the past, challenging dominant or status quo versions of the past. The artistic work with memory activate and animate archives and by allowing them to travel and migrate, they create networks of connectivity that challenge the monumentalization of memory.

One of the crucial concepts raised was that of POSITIONALITY: were are we respect to past violence or slow ongoing violence of neoliberalism? What kind of memory work advances political engagement and responsibility?

When coping with trauma and horror embedded pasts, memory practices become critical to render visible the violence. Memory practices as studied by the group articulate different forms of visibility and invisibility. Art and cultural memory practices enable/encourage/make possible different forms of efficacy, mobilizing action for the future in different levels.

Efficacy may be considered from different perspectives, as a political efficacy that mobilizes social change, but also as a communicative efficacy that by contagion, empathetic connection and affect circulation create collective identities and networks and may subtly transform materials and perceptions. The group discussed to what extent the circulation of affect alone may cause social change.

Another issue discussed in the group was the distinction between empathy, identification and solidarity (between people and networks). We could realize how in acts of scholarship and artistic creation there are various uses of empathy, distance, identification, alienation, solidarity and witnessing. Each of them portrait different sorts of efficacy

When discussing about efficacy we questioned ethical issues regarding for instance the risk of appropriation of artists of painful memories and again the question of positionality: were are we, what is our political and ethical engagement regarding past or present violence?

The different case studies displayed a range of memory practices in different SCALES. From micropractices and intimate memory actions to larger actions, sometimes even monumental actions. All of these cases advanced different sorts of efficacy.

The type of efficacy of these practices relate to the media considered as different ways to address memory: the human body, images, sounds, voices, writing. Analyzing these various media we could better understand how memory is transmitted across bodies and generations.

The body appeared in several presentations as a living dynamic archive, both in the generation that suffered violence and in the later generations. Bodies serve to mobilize the horror that cannot be said and also allows us to learn about other’s experiences when we were not there. The body always transmit, so the relation between memory and body is complex and dynamic: memory of the body / memory in the body / the body as memory. One of the critical aspects specially when working with testimonies was the continuity of presence that prefigured the importance of being there, present and presenciando collaboratively.

We also discussed the potentiality of images as mobilizing devices. Images are powerful transmitters/creators of memory and this is something that mass media seem to understand well since they banalize images as a political strategies. Other than the images the sound and voice are also power media to mobilize memories. The voice for instance immediately mark the presence of who’s speaking. Literature, theatre, photography, internet all portray different ways to approach to memories.

By the end of the work group we highlighted the importance of hope. The mobilization of memory always seem to have a hope component, the desire to share, to render visible and to share experiences to enable us to respond to past and present slow violence.

Photos from the Women Mobilizing Memory Workshop II at the 2014 Hemispheric Institute Encuentro held in Montreal, June 21–28.

REFLECTIONS: Debating the “Woman Question” in the New Middle East: Women’s Rights, Citizenship, and Social Justice

At first glance, 2014 does not seem like a banner year for women in the Middle East. We heard that ISIS, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, was requiring female circumcision around Mosul in Northern Iraq (a claim the group denied). A new law regarding domestic violence in Lebanon failed to criminalize marital rape, apparently thanks to conservative religious opposition.

The prevalence and persuasive power of these headlines about women in the Middle East was part of the reason I was so excited to attend a conference last May entitled, “Debating the “Woman Question” in the New Middle East: Women’s Rights, Citizenship, and Social Justice,” sponsored by the Women Creating Change Initiative at Columbia’s Center for the Study of Social Difference and held at the Columbia Global Center in Amman, Jordan.

The conference brought together scholars and practitioners from five Arab countries in addition to the US and UK. Given that my own doctoral work in Middle Eastern history has been inspired by time I spent working with a women’s rights organization in Syria, I was particularly eager to see what this combination of practical expertise and scholarly attention might produce. Coming from the US, where much of what I see and hear about “women in the Middle East” revolves around stereotypes, it was a privilege to join this group of experts as they reflected on some of the issues facing women and the study of women and gender in the Middle East in the complicated aftermath of the Arab uprisings.

Over the course of an intense weekend in Amman, these scholars and practitioners listened carefully to one another across political, strategic, and theoretical divides. They discussed, on the basis of their close knowledge of the histories and present circumstances of gender politics in particular countries, a set of big questions: How best can women fight for better lives and livelihoods under dire conditions, faced with the intransigence of state power, neoliberal restructuring, and colonial violence in both its historical and contemporary forms? How do discursive traditions or resources, like the languages of human rights, Islam, and shari’a law, enable and constrain women and those who advocate on their behalf?

One striking development is that a debate over the “woman question” itself emerged. How, many asked, does it serve us to pose questions and build alliances in terms of “women” and “men,” rather than in terms of class, race, sexuality, or one of the many other kinds of difference that divide human experience? For example, if thinking only in terms of “women” prevents middle-class feminists in Jordan from supporting the demands for a living wage articulated by working-class women as well as men, might it serve us to think more broadly in our scholarship as well as in our political work?

Focusing on women’s experiences, however, did open up an important conversation around the role of law in securing better lives for women. While many had successfully deployed legal strategies and means to further their political and feminist agendas (for example, taking on torture in Egyptian prisons or advocating for women’s concerns to be reflected in the text of the Egyptian Constitution), others were more critical of the law as a panacea. For example, a legal scholar from Palestine argued that, surprisingly, the transition from shari’a courts to civil courts, while presented as a victory for “women’s rights,” may have actually made it more difficult for women to access justice in the courts.

The conversation about the advantages and unexpected consequences of relying on legal strategies and the language of “women’s rights” started out as a conversation about feminist strategy—when and under what circumstances to deploy the language and practice of the law. It became, however, a much larger conversation about the nature of political intervention. Who intervenes, on behalf of whom, and on what grounds? This question elicited a range of responses, but each was grounded in a particular set of political struggles and ethical commitments--making clear that while it is possible and indeed productive to talk about regional transformations, specific knowledges of embodied realities, political dynamics, and historical contexts are key to the questions which motivate and emerge from feminist scholarship and practice.

The workshop convinced me that it these specific knowledges and the conversations they enable that will allow us to move past the stereotypes which so often characterize—and hamper—our approach to the “woman question” in the Middle East.

--Susanna Ferguson

For more information about the workshop and working group, please visit: http://socialdifference.columbia.edu/projects/gender-religion-and-law-muslim-societies

NY TIMES OP-ED: "The Trouble with Too Much T"

In 2009, the South African middle-distance runner Caster Semenya was barred from competition and obliged to undergo intrusive and humiliating “sex testing” after fellow athletes at the Berlin World Championships questioned her sex. Ms. Semenya was eventually allowed to compete again, but the incident opened the world’s eyes to the process of sex testing and the distress it could bring to an athlete who had lived her whole life as a girl. When an endocrinologist, a gynecologist and a psychologist were brought in to determine whether the teenager was really a woman, she simply asserted, “I know who I am.”

From 2011, major sports governing bodies, including the International Olympic Committee, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association and the International Association of Athletics Federations, instituted new eligibility rules that were intended to quell the outrage over the handling of the Semenya case. Instead, as recent cases attest, they may have made things worse.

Rather than trying to decide whether an athlete is “really” female, as decades of mandatory sex tests did, the current policy targets women whose bodies produce more testosterone than is typical. If a female athlete’s T level is deemed too high, a medical team selected by the sport’s governing bodies develops a “therapeutic proposal.” This involves either surgery or drugs to lower the hormone level. If doctors can lower the athlete’s testosterone to what the governing bodies consider an appropriate level, she may return to competition. If she refuses to cooperate with the investigation or the medical procedures, she is placed under a permanent ban from elite women’s sports.

The first evidence of this new policy in action was published last year in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. Four female athletes, ages 18 to 21, all from developing countries, were investigated for high testosterone. Three were identified as having atypically high testosterone after undergoing universal doping tests. (They were not suspected of doping: Tests clearly distinguish between doping and naturally occurring testosterone.)

Sports officials (the report does not identify their governing-body affiliation) sent the young women to a medical center in France, where they were put through examinations that included blood tests, genital inspections, magnetic resonance imaging, X-rays and psychosexual history — many of the same invasive procedures Ms. Semenya endured. Since the athletes were all born as girls but also had internal testes that produce unusually high levels of testosterone for a woman, doctors proposed removing the women’s gonads and partially removing their clitorises. All four agreed to undergo both procedures; a year later, they were allowed to return to competition.

The doctors who performed the surgeries and wrote the report acknowledged that there was no medical reason for the procedures. Quite simply, these young female athletes were required to have drastic, unnecessary and irreversible medical interventions if they wished to continue in their sports.

Many conditions can lead to naturally high testosterone, including polycystic ovarian syndrome or an ovarian tumor during pregnancy, but women with intersex traits tend to have the highest T levels. And it is these intersex traits that sports authorities want “corrected.”

Sports authorities argue that screening for high T levels is needed to keep women’s athletics fair, reasoning that testosterone improves performance. Elite male athletes generally outperform women, and this difference has been attributed to men’s higher testosterone levels. Ergo, women with naturally high testosterone are thought to have an unfair advantage over other women.

But these assumptions do not match the science. A new study in Clinical Endocrinology fits with other emerging research on the relationship between natural testosterone and performance, especially in elite athletes, which shows that T levels can’t predict who will run faster, lift more weight or fight harder to win. The study, of a sample of 693 elite athletes, revealed a significant overlap in testosterone levels among men and women: 16.5 percent of the elite male athletes had testosterone in the so-called female range; nearly 14 percent of the women were above the “female” range.

This finding undermines the idea that sex-linked performance differences are mainly because of testosterone. The authors suggest that lean body mass, rather than hormone levels, may better explain the performance gap. They also conclude that their research makes the I.O.C.’s testosterone-guided eligibility policy for women “untenable.”

Some might argue that the procedures used to lower T levels are simply part of the price athletes must pay to compete at the elite level. But these choices aren’t temporary hardships like training far from home or following a rigorous diet. The required drug and surgical treatments are irreversible and medically unjustifiable. Clitoral surgery impairs sexual function and sensation; gonadectomy causes sterility; and hormone-suppressive drugs have side effects with potentially lifelong health risks.

Moreover, the policy places a disproportionate burden on poor women who may have limited career opportunities and are likely to face enormous pressure to submit to these interventions in order to continue their athletic careers. Under the current policies, more and more female athletes with naturally high T levels will be confronted with these harsh choices — and not just at the elite level. The I.O.C. requires that each country’s Olympic committee investigate cases of female athletes with high T levels before naming them to national teams. Some countries, like India, now apply such policies to all female athletes, not just those competing internationally.

Barring female athletes with high testosterone levels from competition is a solution to a problem that doesn’t exist. Worse, it is pushing young women into a choice they shouldn’t have to make: either to accept medically unnecessary interventions with harmful side effects or to give up their future in sports.

--Rebecca Jordan-Young and Katrina Karkazis

Katrina Karkazis is a senior research scholar at the Center for Biomedical Ethics at Stanford University. Rebecca Jordan-Young is project director of the Science and Social Difference working group and Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Barnard College. This op-ed first appeared in the NY Times on April 10, 2014.

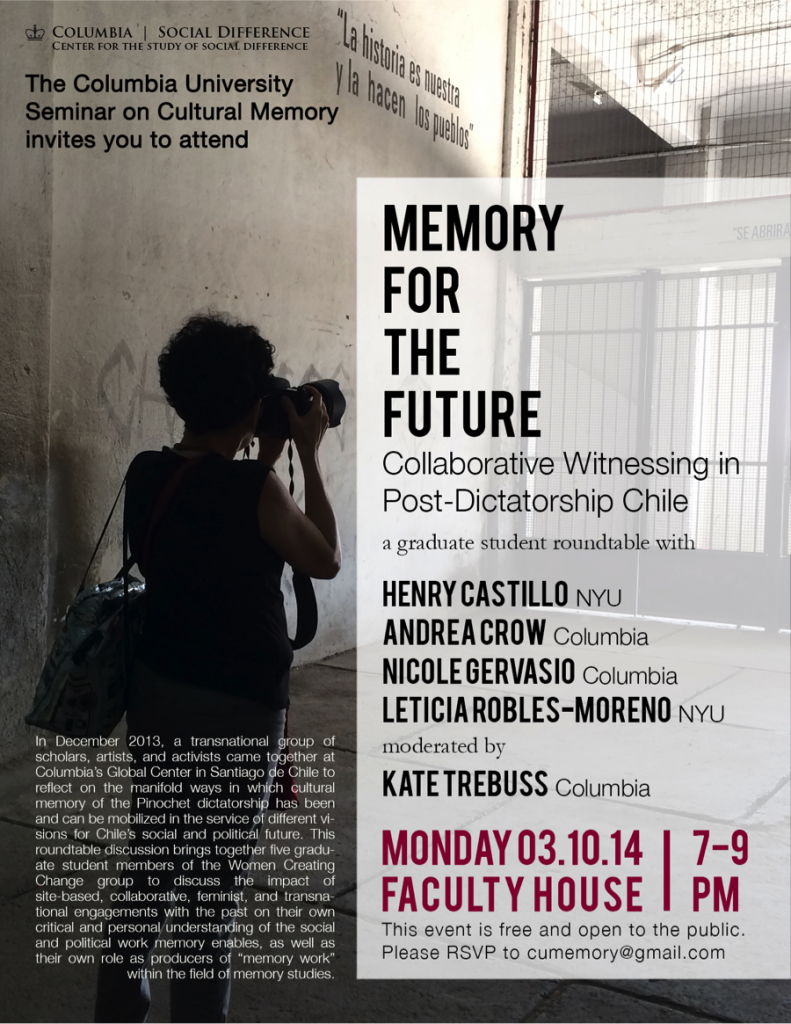

Memory for the Future: Collaborative Witnessing in Post- Dictatorship Chile

In December 2013, a transnational group of scholars, artists, and activists came together at Columbia’s Global Center in Santiago de Chile to reflect on the manifold ways in which cultural memory of the Pinochet dictatorship has been and can be mobilized in the service of different visions for Chile’s social and political future.

This “workshop,” sponsored by Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Social Difference’s “Women Creating Change: Mobilizing Memory” project, incited all members of the group to think not only about the politics and performances of memory in Chile and beyond, but also about their own scholarly practices and methods for engaging with sites of memory and the complex connective histories of which such spaces are a part.

This roundtable discussion brought together five graduate student members of the Women Creating Change group to discuss the impact of site-based, collaborative, feminist, and transnational engagements with the past on their own critical and personal understanding of the social and political work memory enables, as well as their own role as producers of “memory work” within the field of memory studies.

Graduate student roundtable discussion with:

Henry Castillo (NYU)

Andrea Crow (Columbia)

Nicole Gervasio (Columbia)

Leticia Robles-Moreno (NYU)

and moderated by Kate Trebuss (Columbia)

Parenting, Narrative, and our Genetic Futures

Part of the Heyman Center’s Disciplines Series: Evaluation, Value, and Evidence, authors Alison Piepmeier, George Estreich, and Rachel Adams took up many of the questions raised in their November 2013 event on "Genes, Children, and Ethics" (featuring Michael Berube, Faye Ginsberg, and Rayna Rapp) in their discussion of "Parenting, Narrative, and Our Genetic Futures." Elizabeth Emens chaired.

Participants

Alison Piepmeier

Associate Professor of English and Director of Women's and Gender Studies Program, College of Charleston; author of "Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism" and other works.

George Estreich

Author of "Textbook Illustrations of the Human Body" and "The Shape of the Eye"

Rachel Adams

Professor of English and Comparative Literature

Columbia University

Elizabeth Emens

Professor of Law

Columbia University

- Rachel Adams