2026 Theme: Renaissance

Commemorative events celebrating 250 years since the US’s founding are presently underway. These coincide with an ongoing conservative push to rewrite US history - executive orders aimed at ‘ending radical indoctrination’ in schools, reviving a commission to foster patriotism in education, and prescribing the content produced by national history museums and sites. Such a push constructs the past as sacrosanct and injustices as incidental (Neem), modeling the future as a continuation of exalted legacies.

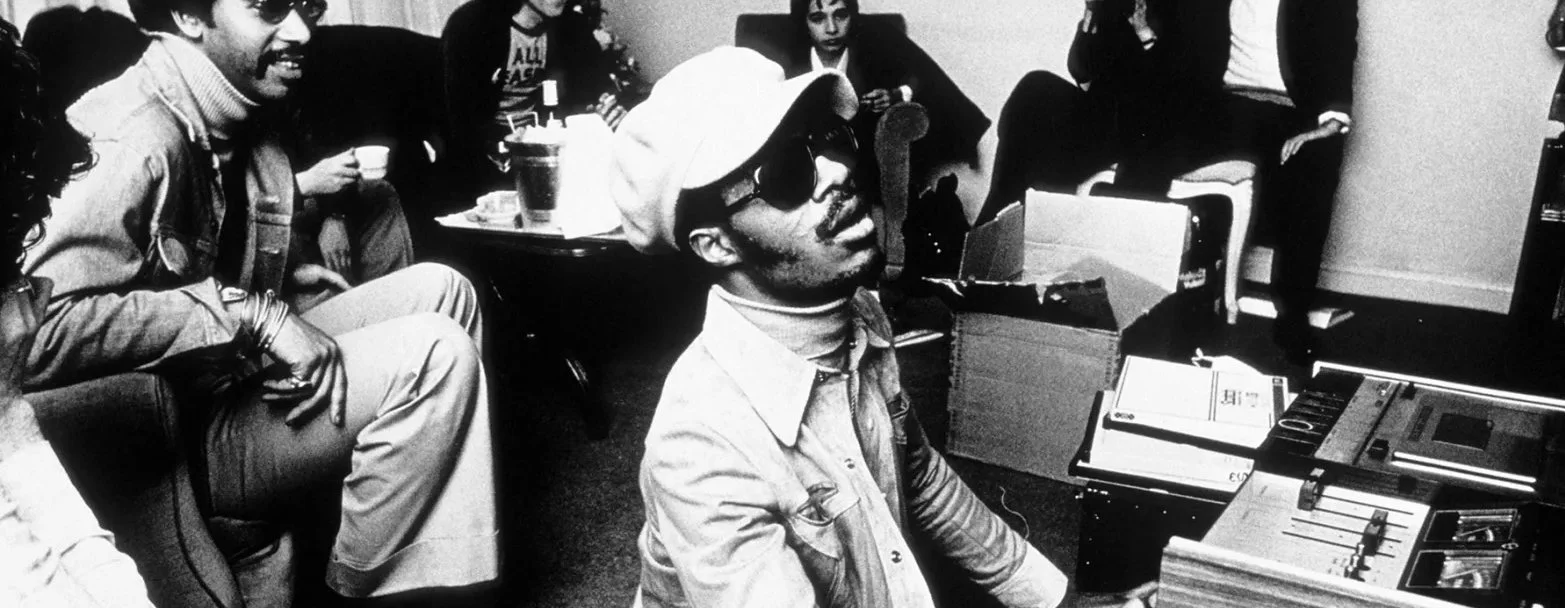

Yet other anniversaries provide an alternate lens onto that very same past. In response to systematic lynchings and everyday terror against African-Americans, the Harlem Renaissance, which recently marked its 100th anniversary, aimed to counter racist stereotypes and promote racial pride through foregrounding African-American arts and culture (Lewis; Smithsonian). Stevie Wonder’s groundbreaking Songs in the Key of Life, released at the time of the US bicentennial and turning 50 in 2026, not only revolutionized music through its genre-bending sounds but critiqued the inequalities and fragmentation plaguing society in songs like “Village Ghetto Land” and “Love’s in Need of Love Today.” Wonder also warned of those “spending most their lives living in a pastime paradise” and “wasting most their time glorifying days long gone behind” (Frieman; Wonder). And last but not least, Robin Kelley’s influential Freedom Dreams—25 next year—provided an inspirational re-reading of past radical social movements, which, while falling short of achieving their political ends, Kelley argued, nonetheless, offer in their visions and ideals, threads from which to weave new dreams and struggle again (Kelley).

Stevie Wonder backstage at the Rainbow Theatre in London. Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns.

For our 2026 call, CSSD takes as its starting point the openings for reassessment and rebirth - for Renaissance - that such commemorative occasions collectively present.

Our invitation to engage with renaissance does not entail a wish for a return to some nostalgically glorified time, as some renaissances have sought. Rather, it is based on a conviction in the continuous potential for rebirths that all presents hold, and on the equally-held belief that such rebirths require not an eschewing of the past or its replication, but a serious, critical, and future-minded engagement with its mixed legacies. This year, CSSD invites applications from working groups aiming towards social rebirth by thinking anew narratives about the past. Taking another cue from Kelley, the Center, in particular, seeks groups that think about not just “what they are fighting against” but consider “what are they fighting for” (8). In short, CSSD aims to reflect, through its chosen working groups, on questions such as: Which aspects of inherited pasts require caretaking and reinvigoration, and which require abandonment in order to develop ways to move forward - to be reborn? What methods of remembrance and reckoning with the past’s legacies move us beyond coercive nostalgia or sanitized and obscuring histories?

Such sought-after reassessments of the past will inherently entail unlearning. The Center thus encourages proposals that in their revisitations seek to upend inherited traditions and common sense values like freedom, democracy, and liberalism to name a few. From Paulo Freire’s emphasis on achieving ‘critical consciousness’ to bell hooks’ exhortation for ‘teaching to transgress’ and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s call to ‘decolonize the mind,’ scholars have foregrounded the significance of intellectual emancipation work for building liberatory futures; these realizations have been taken up and put into practice both inside and outside the academy and all across the globe. While inspired in 2026 by events in its immediate US context, CSSD warmly welcomes applications that grapple with the historical legacies, intellectual traditions, and plethora of social justice movements and renaissances that developed between and far beyond US shores - from the Arab Renaissance of the late 19th to the early 20th centuries to the African Renaissance espoused by Cheikh Anta Diop in the mid-20th.

As ongoing crises, which CSSD took up in its theme in 2025-2026, make the present increasingly unlivable, the question of renaissance becomes ever more critical. To quote a song from yet another Stevie Wonder album, With a Song in My Heart, we are asking working groups to: “Dream when you're feeling blue. Oh, dream, that's the thing to do.”

Citations

“A New African American Identity: The Harlem Renaissance.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/new-african-american-identity-harlem-renaissance.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

Diop, Cheikh Anta. Towards the African Renaissance: Essays in African Culture and Development, 1946–1960. Translated by Egbuna P. Modum, Karnak House, 1996.

El‑Ariss, Tarek, editor. The Arab Renaissance: A Bilingual Anthology of the Nahda. Modern Language Association of America, 2018.

Freiman, Scott. “40 Years Later, ‘Songs in the Key of Life’ Is as Fresh as Ever.” CultureSonar, 29 Sept. 2016, www.culturesonar.com/songs-in-the-key-of-life-40th-anniversary/.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos, Continuum, 2000.

Kelley, Robin D. G. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Beacon Press, 2002.

Lewis, David Levering. When Harlem Was in Vogue. Alfred A. Knopf, 1981.

Neem, Johann. “Bringing American History Back Home for the 250th.” Perspectives on History, American Historical Association, 14 July 2025, historians.org/perspectives-article/bringing-american-history-back-home-for-the-250th/.

Wa Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Heinemann, 1986.

Wonder, Stevie. “Dream.” With a Song in My Heart, Tamla Records, 1963.

Wonder, Stevie. Songs in the Key of Life, Tamla Records, 1976.