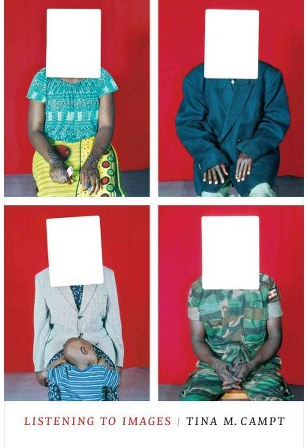

FORTHCOMING: Tina Campt's "Listening to Images" Investigates Archive of Photos of Black Diaspora

Tina Campt's Listening to Images, soon to be published by Duke University Press, was originally conceived in the CSSD project she co-directed called Engendering the Archives.

Throughout the book, Campt tunes in to the affective frequencies inherent in various photographs of the black diaspora. Images range from late nineteenth-century ethnographic photographs of rural African women and photographs taken in an early twentieth-century Cape Town prison to postwar passport photographs in Birmingham, England and 1960s mug shots of the Freedom Riders.

Read more about the book here.

PANEL DISCUSSION: Gender Roles, Violence and the Refugee Experience in Mexico, the United States, and the European Union

In February, CSSD’s Reframing Gendered Violence working group presented a panel discussion on “Refugees and Gender Violence: Vulnerability and Resistance” that addressed the current conditions of forced migration in various parts of the world and the formations around gender roles and gendered violence it has created.

Wendy Vogt, Professor of Anthropology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, discussed “Rape Trees, State Security and the Politics of Sexual Violence along Migrant Routes in Mexico.”

Vogt said that along the U.S./Mexico border, Central American immigrants have become simplistically associated with sexual violence and thus used as scapegoats for the consolidation of U.S. political power. Vogt claimed that actually half of all sexual assaults happening at the border are perpetrated by migration employees and not migrants.

Vogt said that a series of assumptions and biases against migrants are employed to justify draconian governmental policies. At the local level, migrant men are customarily viewed as sexual predators and criminals while migrant women are considered suspect as sex workers. Migrant shelters then become marked as alleged rape sites, receiving complaints and threats from local populations, all of which then legitimizes militarized police tactics against migrants. Similarly, conservative news outlets on the national level have reported on “rape trees” along the border that are hung with the undergarments of the alleged victims of rapes perpetrated by Mexican criminals and “coyotes.” These unsubstantiated stories proliferate and are used to confirm the suppositions of sexual violence perpetrated by encroaching migrants.

“Such discourses allow the re-inscription of the US nation as chaste, while erasing the complicity of the US government in long term policies that have caused migration,” said Vogt.

Diana Taylor, University Professor of Performance Studies and Spanish and Founding Director, Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics, NYU, discussed the Madres of Central American Migrants movement.

Starting in the 1970s, these traveling “caravans” of mothers and families of the thousands of Central American migrants who have disappeared as they travel through Mexico on their way to the United States aim to connect families of the missing migrants and raise awareness about their fates. The Madres also speak to the United States’ increased attempts at controlling the tide of migrants coming from Mexico.

Stopping at local jails, brothels, and detention centers, caravans embark on fact-finding missions and have become a crucial part of the human rights strategy in Central and South America, said Taylor.

One key way in which the Madres functions is to create a meme—an image, a movement, a story—that transmits the grief and trauma involved in a direct fashion that is both simple and replicable. Successful memes like the Madres materialize everywhere U.S. state policy is used to “disappear” unwanted individuals. The militarized border, changing labor laws, and the war on terror were all cited as examples.

Taylor said the Madre movements have produced signs of hope, as in Argentina, where many of the people responsible for political killings there have been exposed and imprisoned.

Chloe Howe Haralambous, graduate student in English & Comparative Literature, Columbia University, spoke about “Suppliants and Deviants: Gendering the Refugee/Migrant Debate on the EU Border.”

Haralambous said that recognition of refugee status is the only guarantee of entry into Europe and that those individuals labeled economic migrants are not given that privilege. For example, in the current refugee crisis, unwanted Iraqi and Afghan immigrants have been treated as economic migrants in an attempt to artificially reduce the number of people Europe must protect, she said.

While women are considered “less dangerous” and are usually guaranteed entry over young men, “There is no distinction between helpless refugees and unworthy migrants,” Haralambous protested.

This sorting by gender leads to unfortunate results, such as half of the victims of sexual assault in refugee camps turning out to be young men and women sometimes disowning their husbands so they can improve their odds of gaining entrance. Thus, the refugee is characterized as grateful and helpless while the economic migrant is imagined as sneaky and undeserving, said Haralambous.

“In the mainstream, you are either a compliant and suffering refugee or a rapacious economic refugee,” she said.

Isin Önol, Curator in Vienna and Istanbul, spoke about her exhibit, “When Home Won’t Let You Stay: A Collective Deliberation on Taking Refuge.”

The show attempts to elucidate the journeys of the displaced between their lost homes and the new ones they will have to build, said Onol, but it also seeks to bring people of disparate experiences together.

“It interrogates what it means to be human today, in contrast to the ideals of humaneness and human rights,” Onol said of the exhibit.

While human beings can excel at organizing for evil, they can also organize for good, she said, referring to the structural violence that newcomers can experience and the experience of those who might remain passive in the face of that violence.

In the Q&A period that followed, the panelists were asked what journalists could do to ameliorate the situation. Haralambous said journalists would do well to address the structural causes behind the refugee crisis, since media contributes to the normalization of these events.

Vogt underlined the fact that traditional gender narratives were also being used to distort the narrative and that this actually enabled compassion fatigue. Instead, “We should point to people’s resilience—we should encourage alliance, not empathy. We should be motivated by the possibility of solidarity,” she said.

Photos from the discussion are posted here and a video of the discussion can be viewed here.

Contributed by Terry Roethlein and Liza McIntosh

PANEL DISCUSSION: Photographers and Journalists Document Gendered Refugee Experience

“In recent days, we’ve seen the supposed prevalence of violence against women in Muslim countries used to justify travel bans and immigration prohibitions,” remarked Jean Howard, George Delacorte Professor in the Humanities, as she introduced Refugees and Gender Violence: Media and the Arts, the latest event in a two-year series on Reframing Gendered Violence, co-sponsored by the Center for the Study of Social Difference, and the Dean of the Humanities.

The unsatisfactory state of affairs noted by Howard inspired the panel’s questions about how journalists and photographers can vivify the precarious realties of refugees, reframing conventional narratives to tell stories that disrupt our clichéd understandings of gendered violence.

A photojournalist based in Istanbul, Bikem Ekberzade spoke to this question in her wide-ranging, revealing presentation, entitled “The Refugee Project: Anatomizing Gendered Violence.” Showing photographs of forced migrations in forgotten conflict zones such as Kosovo and Afghanistan, she illustrated the stories of women stranded midway through their journeys toward refuge and the hope of a better life.

Sarah Stillman, a staff writer for The New Yorker and the Director of the Global Migration Project at Columbia School of Journalism, spoke thoughtfully on the ways that narrative can affect our understanding of gendered violence against refugees. “How can we resist binaries in storytelling, which distinguish between ‘worthy’ and ‘unworthy’ victims?” she asked. “When I think about reporting on gender-based violence in this context, one of the most critical things is to show people in the act of being creative, or loving. That has really stuck with me when I think about the families I’ve gotten to know in the context of my reporting.”

Susan Meiselas, president of the Magnum Foundation and author of acclaimed books such as Carnival Strippers and Nicaragua, built on the themes of the two previous speakers, detailing the challenges and discoveries of her latest project, A Room of Their Own. This collaborative endeavor uses photos, testimonies, and original artwork to document the experiences of women in a haven in the United Kingdom. Of her experience working on the product, she explained, “this is hard…I am making something with, and in some ways for, these women…I am trying to tell a story that is fairly complex, building a path for readers to hopefully care about a place they might not be anywhere near. Can what I’m making help sustain the haven?”

The event concluded with a lively Q & A that featured questions on topics ranging from the practical benefits of artistic intervention to the narrative ethics of the journalistic profession. The conversation will continue next year with segments on gendered urbanisms and the gender of global climate change.

Access photos from the discussion here and videos here.

Contributed by Liza McIntosh

Jackie Leach Scully Discusses Precision Medicine, Embodiment, Self & Disability

On March 9, 2017, Dr. Jackie Leach Scully, Professor and Executive Director of PEALS (Policy, Ethics and Life Sciences) Research Center at Newcastle University in Newcastle, UK, led a thought-provoking and insightful seminar and discussion on "Precision Medicine, Embodiment, Self & Disability" as part of CSSD's project on Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics and Culture.

Dr. Scully largely explored biomedical perceptions surrounding disability, and proposed how these perceptions are and will continue to change within the era of precision medicine. Traditionally, biomedical views have largely considered disability as a nominative and quantifiable pathology with less consideration for cultural, environmental, social, economic and political aspects. And while precision medicine remains rooted in this conventional biomedical perspective, rapid advances in the field are posing new bioethical questions and challenges that will continue to shape not only the biomedical but also the social/societal perceptions of disability.

Dr. Scully dove into a variety of such issues that we are currently facing and those that will likely be forthcoming. For example, paradoxically, individualized probabilistic data of genomic abnormalities obtained in the preconception/prenatal setting can effectively uncouple genetics from physical manifestations (the “walking ill”), thereby resulting in unjust discrimination—where the concept of disability exists prior to the individual’s embodiment and identity have taken form. This challenge reflects the central question of how precision medicine’s attitude toward “disability” differs from that of “disease.” While medicine in general rationalizes the avoidance or elimination of disease, will this rationalization inevitably apply to genetic variation associated with disability? And how will our society come to these decisions regarding what type of genomic variation we consider “abnormal” and appropriate for preconception and prenatal modification such as through preimplantation genetic diagnosis or in the near future, gene editing techniques.

With the surge of funding for precision medicine research over the past three years, Dr. Scully makes the case that we should allocate a portion of this funding to monitor the ethical ramifications surrounding these biotechnological advances in effort to keep up with the rapidly evolving landscape of precision medicine.

Contributed by Liz Bowen

KEYWORDS PANEL DISCUSSION: "Justice" defined in legal, institutional, and environmental terms

On March 23rd, CSSD presented its 2017 Keywords Roundtable Discussion featuring panelists from various departmental homes who discussed definitions of the word “justice.” Rachel Adams, Professor of English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University and Director, Center for the Study of Social Difference introduced the group and commented on the challenges the new presidential administration presented to minority groups like people of color and the LGBT community, calling into question the U.S. government’s commitment to social problems and inequality.

Adams said that for people with disabilities, the legal definition of “justice”—the administration of fairness—posed a problem because the definition for “fairness” varies for those with disabilities. The American democratic social contract does not by nature take into account people whose bodies deviate dramatically from the norm or who might possess different capabilities for autonomy or reasoning, she said.

“Are there ways to revise that definition or are these individuals an add-on to those theories?” asked Adams, pointing out that some minority groups like the disabled need much more assistance in claiming their rights.

Adams said that while the new administration’s threats to the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid, and education all impacted justice for people with disabilities, the surge in public protests also presented problems for those individuals because of their difficulties with mobility, crowds, marching, and speaking. She concluded with a call for “activism for justice when you don’t have a body for protest.”

Kathryn Kolbert, Director of the Athena Center for Leadership, Barnard College, examined “justice” through the lens of U.S. constitutional law, saying that the Constitution provided “multiple and overlapping guarantees” of justice with legal protections of free speech and press; due process and equal protection; and the protection of liberty. While the Trump Administration threatens all of those freedoms, vigilance against incursions against them by any governmental agent is always necessary, she said.

Kolbert said there were four prerequisites that underpin the notion of American justice and all of them are currently being challenged. First, the system of governmental checks and balances keeps political powers in the three branches separate so they won’t unduly influence the administration of justice. “Today they are totally out of alignment,” said Kolbert, citing the Republican domination of the House and Senate as an example.

Kolbert said civil debate was the second guarantee of justice and that the lack of it in current U.S. politics was problematic. Freedom of speech and the press were also crucial measures that were in danger, according to Kolbert, who claimed that “Americans are totally divided over what facts are and over a common set of measurements for determining what is effective,” she said.

The fourth prerequisite for justice that Kolbert cited was access, which is currently being undermined by the huge income disparities within our society. “The gap between the haves and have nots is now so pronounced that one’s access to freedom and institutions of civil society are defined solely by one’s economic status,” she said, citing healthcare as a classic example.

Carla Shedd, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Columbia University presented herself as an urban sociologist who is intrigued by the power public institutions have over people’s lives.

Shedd described the awesome power within the concept of parens patriae—the legal framework through which the state acts as the surrogate parent for its citizens and through which governmental actors are allowed to intervene in the lives of individuals (particularly those in juvenile court) and their families with the ultimate goal of building better citizens.

She also explained the phrase “carceral continuum” a term she uses to describe the expanding systems of social control and punishment that are experienced at different levels of severity according to one’s social status. She said her work explored how societal structures such as neighborhoods, schools, and courts unjustly shape the trajectory of young people’s lives.

“Steeped in the language of justice, and often in the name of protecting America’s poor and vulnerable, the nurturing arm of the state may also operate like an instrument of punishment,” said Shedd. She explained that the institutions mentioned earlier are often used to distribute criminal justice unequally, with racially subordinated groups receiving a disproportionate amount of the carceral system’s punishments.

Jennifer Wenzel, Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature and Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies, Columbia University, discussed her work on justice in relation to the environment and climate.

“Environmental justice…is concerned primarily with environmental racism and the toxic burdens borne disproportionately by racialized minorities,” said Wenzel, explaining that current theorists posit the socially marginalized as receiving few environmental benefits like natural resources but receiving more environmental burdens like pollution. The case is similar with climate change, in which the industrialized Global North is responsible for the production of most of the greenhouse gases on the planet but the most severe effects of climate change are felt in the Global South, she said.

Even in the very definition of environmental justice, hegemonic values and conceptualizations of nature also inform the discussion. Thus, mainstream environmental movements in the Northern hemisphere set the norms, eclipsing the actual, specific environmental concerns of those who are suffering environmental fallout in the Global South.

In conclusion, Wenzel called for an "environmentalism of the poor" that would demand a healthy environment for everyone, not just the poor, and said that “One of my concerns as a scholar-citizen is that this newfound interest in geological stratification threatens to displace attention to social stratification.” Overwhelming concerns about future dystopias that currently dominate mainstream dialogues could displace a more practical focus on present injustices and inequalities affecting people now, she said.

Photos from the roundtable discussion are available here.

Contributed by Terry Roethlein, Communications Manager